Food from the Regency Period: What Did Jane Austen Eat?

This week marks the release of the The Abbey Mystery, the first in Julia Golding’s Jane Austen Investigates series. Based on the life of young Jane during the late eighteenth century, this book is both a perfect introduction to Austen and a delight for those who are already fans of her books. Golding has perfectly captured everything that is so familiar to us from Jane’s works at the same time as widening the scope of what we expect from a story set during the Regency period. I am so pleased to be a part of the blog tour that celebrates this brilliant historical detective story and my book blogging colleagues have featured some wonderful posts already. You can read a review by Scope For The Imagination here and a piece by Golding about the subjects that are not explicitily discussed in Austen’s books such colonialism, politics, the Napoleonic War and slavery on the Federation For Children’s Books website.

But my stop on the tour is all about food and Julia Golding has very kindly taken the time to share the details of what Jane Austen and her contemporaries would have eaten in Regency England. The subject was discussed in the news just this week when Jane Austen’s House Museum announced that they would be updating their displays to ‘include the Regency, Empire and Colonial contexts in which [Jane] grew up and lived’. Tea and sugar during the eighteenth century were products of slavery and colonialism but the museum was criticised for choosing to make these relevant and important additions to their presentation. You can read their statment here.

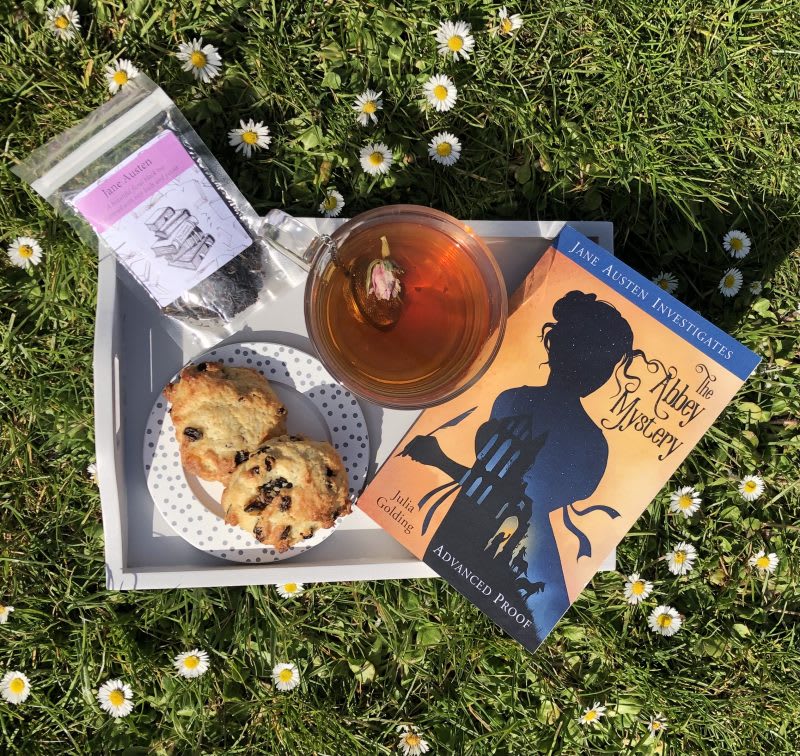

If you want to try some Regency food for yourself I’ve adapted a recipe for ‘rout cakes’ from an original 1822 cookbook and I had great fun making them. These cakes are mentioned in Austen’s classic book Emma and are really easy to bake. You can find the recipe at the bottom of the page but first join Julia as she guides us through the historical food and mealtimes of Jane Austen’s world.

‘Very able to keep a good cook, and that her daughters had nothing to do in the kitchen’ – Regency families and what they ate by Julia Golding

We are what we eat – and we are also how we eat. It is easy to think that breakfast, lunch and dinner is the ‘normal’ way to divide the day up, until you live in another culture. Take Poland, for example, where traditionally it is usual to eat your first breakfast early, second breakfast mid-morning, and the main meal (obiad) – mid-afternoon, and perhaps a supper later on. The Polish example is much closer to what you would have met if you were eating in Jane Austen’s time.

Breakfast

A middle-class family such as Jane’s, living in the country, would probably have breakfast at around 8 or 9 am. Jane was in charge of her family’s tea and sugar, so this was the meal she tended to control. Normal things to eat would be toast and muffins with butter. The big English cooked breakfast of beef and ale was going out of fashion and replaced by this lighter selection, but doubtless beef was still consumed by labourers who could afford meat. They would need the meal to set themselves up to work all day. Poorer people would survive on a penny loaf or porridge and some small beer (water wasn’t generally safe to drink). The very rich could, of course, have lavish breakfasts with a choice of dishes.

Dinner/Main Meal

This came after the working day was done. Typically it might start at 3 pm, though in town it was getting later and later, which posed problems for the owners of the two main theatres who started their performances at 6pm. In Pride and Prejudice the Bennet’s show their relative lack of sophistication by dining much earlier than the Bingley’s (the Bingley’s eat at the very fashionably late 6.30pm). Jane Austen herself was well aware of the judgements, writing teasingly to Cassandra in 1798 from Steventon as her sister was staying with the more fashionable family in Godmersham: ‘We dine now at half after three, & have done dinner I suppose before you begin – We drink tea at half after six – I am afraid you will despise us.’ However, by 1808, she writes, ‘we never dine now before 5.’ Dinner was slipping to a more familiar (to us) time in the day.

In the days before refrigeration and supermarkets, food would be locally sourced so it would follow the seasons. Jane and her family would grow much of their own fruit and vegetables, preserve them for the winter, and even raise their own pigs, chickens and cows. They could afford a cook so the time-consuming tasks, such as bread making, were done by a professional servant. The quote in the title is from Mrs Bennet, who in Pride and Prejudice is rather offended when their visitor, Mr Collins, infers that one of the daughters may have cooked the meal. Perhaps Mrs Austen may have said the same thing! Middle-class women may be expected to know how to cook, but not to do the heavy lifting. Poorer families in the city were unlikely to have their own ovens so would often take meals to be cooked at a local shop, such as a bakery, or buy the Regency version of takeaway food, often in the form of pies and pasties. Pastry was used as we would a plastic bag or container and our closest modern hangover from that is the Cornish pasty with its thick handle of crust.

At the other end of the social scale, if you were attending a formal dinner, the habit was to choose from the nearest dishes and show your good manners by offering it to your neighbour. There were several covers – or sets – of dishes, mixing sweet and savoury. These were laid out then removed and replaced by a new course. Cassandra Austen attended a dinner in 1798 with twenty-five dishes, details of which are given in R W Chapman’s edition of Jane’s letters. Here is what Cassandra was treated to: Salmon, Trout, Soles, Fricando of Veal, Rais’d Giblet Pie, Vegetable Pudding, Chicken, Ham, Muffin Pudding, Curry of Rabbits, Preserve of Olives, Soup, Haunch of Venison, Open Tart Syllabub, Rais’d Jelly, Three Sweetbreads, Larded Maccaroni, Buttered Lobster, Peas, Potatoes, Baskets of Pastry, Custards and Goose.

There are some false friends here: jelly is not the highly coloured sort we think of, but made from gelatin and could be sweet or savoury; and sweetbreads are a form of offal. Ladies were expected to nibble while gentlemen could pile their plates high. French cooking was in fashion and new tastes were coming in from the empire so the food was rich and far from bland. All of it would be fattening so it was as well dresses had such high waistlines!

Nuncheon

The slippage of dinner to a later time brought in nuncheon, or lunch, to bridge the gap between breakfast and dinner, and usually took the form of a sandwich or cold meat. It is perhaps indicative that Jane didn’t quite trust this innovation because it is the unreliable Willoughby who partakes of this in Sense and Sensibility.

Afternoon tea

Tea was most often drunk after dinner and at breakfast but the increasing gap between meals meant the great institution of the afternoon tea was creeping in (but not taking root until the 1840s). Its origin was in the custom of offering refreshments to any caller who paid a morning call (which actually went well beyond noon), just as Lizzy and her aunt and uncle are when they visit Pemberley: ‘cold meat, cake, and a variety of all the finest fruits in season…beautiful pyramids of grapes, nectarines, and peaches’. Jane must have been describing here her idea of a perfect snack in her most desirable house.

Supper

As dinner was still for many in the mid-afternoon, many people were peckish by the evening, so some had the habit of a late supper. Balls and entertainments provided refreshments because they knew people would be hungry by that time and would need the energy to dance until the small hours.

You can see what recipes Jane might have tasted in her friend, Martha Lloyd’s book. Long after Jane’s death, Martha went on to marry Jane’s brother, Francis. She collected the favourites from among family and friends. The book includes home remedies, perfumes and household tips, showing how close the kitchen was to the still room and other forms of potion making.

I had great fun when writing Jane Austen Investigates imaging how the young Jane would have reacted to be invited a dinner very like the one her sister went to in 1798. You can imagine the thirteen-year-old’s eyes widen as dish after dish was placed before her at Southmoor Abbey.

Thank you so much to Julia Golding for taking the time to share such amazing expertise. To find out more about her and her work you can visit goldinggateway.com and follow her on Twitter @jgoldingauthor. Thanks also to Lion Hudson for sending me an advance copy of The Abbey Mystery.

Recipe for Regency Rout Cakes

This recipe appeared in ‘The Cook and Housekeeper’s Dictionary‘ by Mary Eaton in 1822. She wrote:

‘To make rout drop-cakes, mix two pounds of flour with one pound of butter, one pound of sugar, and one pound of currants, cleaned and dried. Moisten it into a stiff paste with two eggs, a large spoonful of orange-flower water, as much rose water, sweet wine, and brandy. Drop the paste on a tin plate floured, and a short time will bake them.’

I’ve made some adjustments to the recipe for the purposes of this blog, mostly because two pounds of flour would make an awful lot of cakes but also because orange-flower water and rose-water are not always easy to come by.

Ingredients:

150g plain flour

75g butter

75g sugar

75g currants

One egg

One tablespoon each of rose water, orange flower water and brandy (I substituted all of these with orange juice and some drops of orange essence because I didn’t have the first two items in my cupboard and I also chose to keep the brandy away from my tiny taster).

- Mix the butter, flour and sugar together. You can do this in a food mixer but rubbing them together with your fingers is a great way to get little kitchen helpers involved.

2. Add your currants (I used mixed fruit because I had some in my cupboard left over from Christmas).

3. Mix in the egg with whichever liquids you have chosen to use.

4. Mary Eaton finishes her recipe with the wonderful instruction ‘Drop the paste on a tin plate floured, and a short time will bake them’. I dolloped generous tablespoons of the mixture onto a parchment-lined baking tray and put them into the oven at 200c.

5. After 15 minutes of watching them carefully they were golden brown and smelled amazing.

6. Enjoy your rout cakes with a cup of tea and a really good book. They are delicious and I might have scoffed two while I set up the following picture.

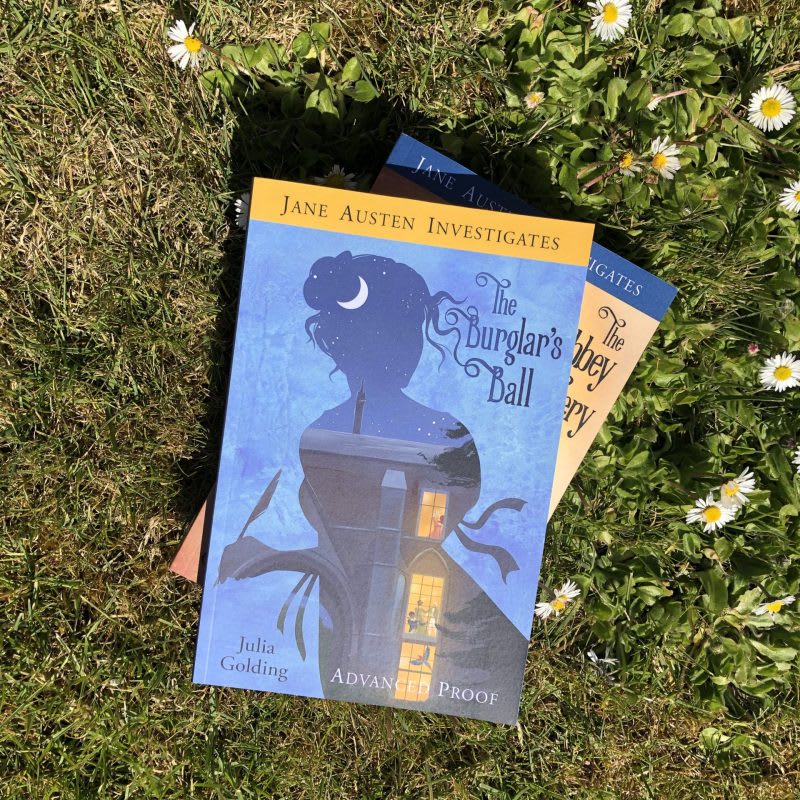

The next book in the Jane Austen Investigates series is called The Burglar’s Ball and is available for preorder now.

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links to bookshop.org and will redirect you to their website. If you make a purchase I will make a very small commission at no extra cost to you and they also share their profits with independent bookshops around the UK.