Interview with The Last Hawk author Elizabeth Wein

I recently had the opportunity to review the latest book by Carnegie Award nominated author Elizabeth Wein. The Last Hawk is about 1940s wartime aviation from the viewpoint of fictional German glider pilot Ingrid Hartman. It takes the reader deep into the world of Luftwaffe test pilots while revealing the horrific acts carried out by the Nazis during the Second World War. The level of historical detail is fantastic and I was fascinated by the author’s decision to tell a story from a German viewpoint. Elizabeth agreed to chat with me about the inspiration behind her book and the research that inspired Ingrid’s tale.

Your latest book, The Last Hawk, tells the story of Ingrid, a young German woman who flies gliders as propaganda for the Nazis. Why did you decide to write a story from the point of view of someone who worked for the Luftwaffe?

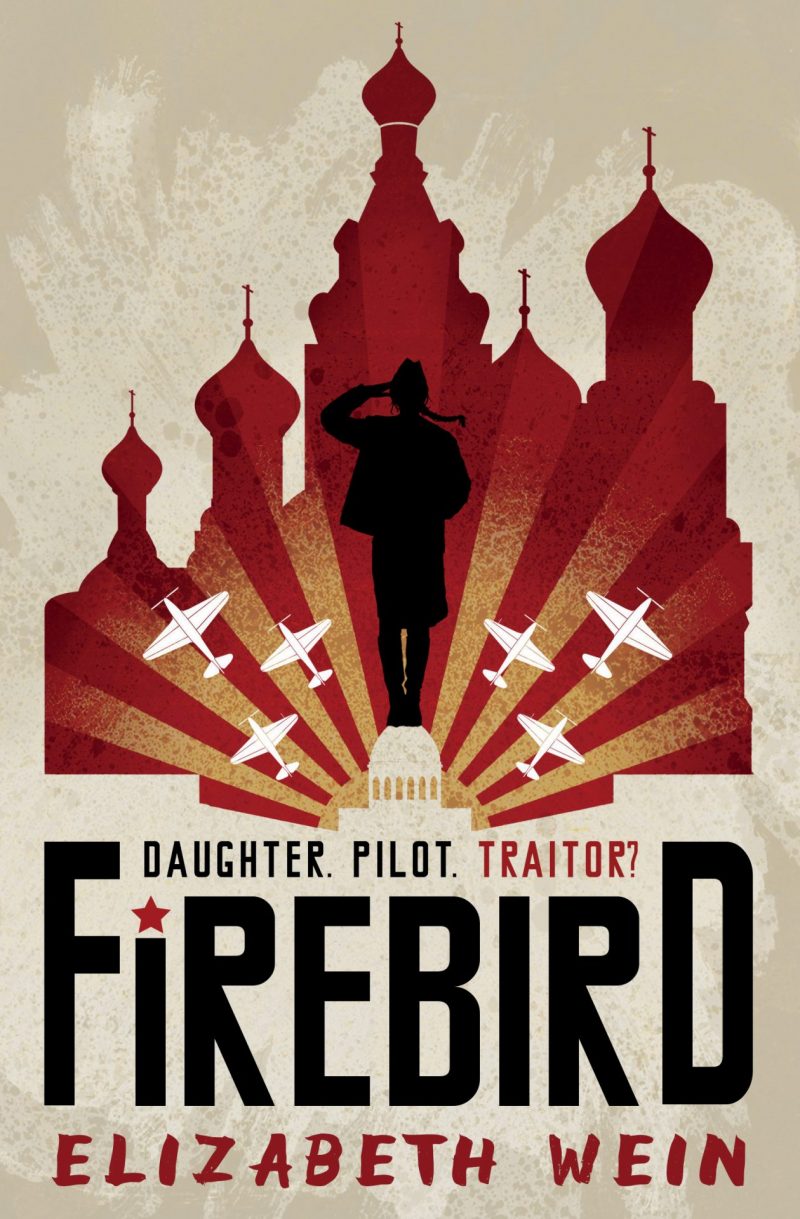

There were two reasons. After I’d written Firebird, in which Germany invades Russia, and White Eagles, in which Germany invades Poland, I felt as if I needed a book attempting to show a German point of view to try to round things out. The other reason is that for some time I’d been fascinated with Hanna Reitsch, Germany’s incredible female test pilot of the 1930s and 1940s. Using Ingrid as a point-of-view character gave me a chance to give a fictional twist to a little of Hanna’s story.

Early in the book it is clear that Ingrid is not only aware of the brutality of the Nazi party but that she also lives in fear of it. As her own fear becomes overshadowed by her discovery of the scale of the atrocities that the Nazis are carrying out, she questions her own place and what she is willing to sacrifice. How difficult was it to strike a balance between showing a character who questioned the brutality of the regime but not to mislead the audience into thinking that everyone who served the Nazis did so out of fear?

This is something I’ve had to struggle with before, so maybe that experience helped! In writing my non-fiction book A Thousand Sisters: The Heroic Airwomen of the Soviet Union in World War II, I felt that I had to get inside the mindset of the Russians who lived through Stalin’s “Great Terror” before I could understand their baffling mix of patriotism and fear. I did a lot of research on the Soviet Union in the 1930s, and the bottom line is that people seem to be able to separate their love for their country from their fear of a terrifying regime. It means that some people are willing to serve their country – proudly and honestly – hoping for better things for their nation, while perhaps not always agreeing with the government in charge. And a dictatorial leader is actually pretty good at stirring up patriotism, even if it’s for the wrong reasons.

In Ingrid’s story, I think that details such as her love for the beautiful landscape of the Alps where she grows up, and her appreciation of literature, nature, and national heroes, help the reader to understand why she’d want to serve her country, without downplaying her growing awareness of the horror that the Nazi regime brings to Germany.

I’m fascinated by the research you carried out into the Luftwaffe and Hanna Reitsch? Where did you begin and did you meet any difficulties researching the history of the defeated side of a war?

There’s a lot of easily accessible information about Hanna Reitsch, including an autobiography (available in English as The Sky My Kingdom), an excellent biography by Judy Lomax called Hanna Reitsch: Flying for the Fatherland, and video interviews of Hanna herself filmed in the 1970s (you can watch that video below).

She really is a charismatic writer and speaker! There’s also a ton of information available about the Luftwaffe. The more difficult research concerned the Nazi eugenics programmes, and their attitude towards stuttering. The internet is a hugely helpful resource. I often spend far too long watching 1930s videos of German flight school gliders taking off, and reading recipes for coffee substitutes in Germany during the war. While writing this book I acquired a taste for Scho-Ka-Kola, the aviator chocolate that Ingrid’s friend Emil shares with her – it’s still made and still sold in an iconic round red tin!

One of the rabbit holes I fell into while researching this book had to do with the thread in which Ingrid reads Wind, Sand & Stars by Antoine de St. Exupéry. I was utterly delighted to discover, via Wikipedia in English, French, and German, that it was published in Germany in the 1930s under the same title as in English (translated into German, of course – but had it been a translation of the original French title, Terre des Hommes, it wouldn’t have been immediately recognizable in English). In trying to discover whether the book had been widely read in Germany, I was led to a French book by the journalist Jacques Pradel and the diver Luc Vanrell. St-Exupéry: L’ultime secret – Enquête sur une disparition (“The ultimate secret: an inquiry into a disappearance”) is about the recent discovery of the remains of St. Exupéry’s aircraft, shot down in 1943 in the Mediterranean, and contains an interview with Horst Rippert, the Luftwaffe pilot who shot him down. Rippert’s interview was full of wonderful little glimpses of what it was like to be a young German pilot during the 1930s and 1940s.

The short answer is that I do most of my digging on the internet, which eventually uncovers a gem of a book or academic article that gives me the answer I’m looking for.

The German word Vergangenheitsbewältigung refers to the process of coming to terms with the past and working through the traumatic events for which certain groups were responsible. Education about the Nazis and the Holocaust is mandatory within the German school curriculum today. Do you think that books like The Last Hawk can support this process of learning about and from the past?

I certainly hope so – of course that is part of the reason I tell these stories, and I believe deeply that the lessons of the past are timely and applicable today. When I was writing my novel Rose Under Fire, which partly takes place in the women’s Nazi concentration camp at Ravensbrück, I attended a week-long seminar at the Ravensbrück Memorial and was really struck by the serious and thoughtful respect that the German students on the seminar expressed towards Holocaust education. I was also stunned to hear that, along with the Spielberg classic Schindler’s List, they’d all had to watch an American NBC television miniseries from the 1970s called Holocaust. I too had watched this as a young teen when it was first broadcast. I’d loved it, but it was so stylized and obviously a fictional story (it starred a very young Meryl Streep!) that it never occurred to me it could be used as an educational tool. So that was eye-opening to me – even though, as a fiction writer, I was working fiercely at using fiction to “tell the world” the tragic story of the women of Ravensbrück.

The Ravensbrück seminar was focused on memory and the representation of memory, and one of the things we discussed was how true stories are coloured and altered by our telling of them. Often, what’s important to take away from a story is the meaning, rather than the details. So yes, I feel strongly that my books, and other historical fiction, can support this process. But I also feel that it’s important not to be lured into accepting fictional accounts, such as Ingrid’s flight in the Me-328 parasite plane, as historical reference material.

Firebird, White Eagles and The Last Hawk are all books about the Second World War and they tell stories from Polish, Russian and German perspectives. Most of the films we see and books we read about the war are told by British or American protagonists. What are your thoughts on giving voice to these underused but vitally important different national experiences?

Well, I confess that I’ve also written three other war stories that do have British or American protagonists! For me, it’s partly a cultural issue, as I don’t always feel confident getting in the head of a young person from an unfamiliar background. But as I’ve expanded my research and knowledge of World War II, I’ve found there are a lot of stories that I’m burning to tell, and I’m developing an increasing awareness of how to tell them. For example, doing non-fiction research on the female pilots of the Soviet Union gave me a much deeper understanding of the headspace they were coming from. I don’t think I’d have been able to write Firebird without that knowledge.

I’ve always been interested in telling little-known stories – one of my books, Black Dove, White Raven, is about the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1935! And given the global nature of World War II, it feels very right to me to pick up some of the lesser known but nevertheless fascinating threads of the war and bring these stories to a wider audience.

Why did you want to show the Second World War from the perspective of women who took military roles?

I don’t really think of myself as writing about the military so much as writing about aviation. During the Second World War, aviation and the military were very closely intertwined. And what’s easy for us to forget is how many of the combatants were “citizen soldiers” – mostly, these weren’t career military women (or men) or reservists; they were people who put aside their careers or their education or their families to fight in a time of great crisis. I think I am intrigued by the idea of ordinary people being called on to do extraordinary things. For the women of the 1940s, it was even more extraordinary for them to be in the air than for the men – their story is less often told – and that’s what draws me to it.

As well as their involvement in the war, all of your leading characters share a love of flight. Why did you choose to write about wartime pilots?

I got a private pilot’s license in 2003, and while I was learning to fly I really wanted to write about flying. At first I wrote short stories, and eventually a novel (Code Name Verity). At the aero club where I learned to fly I was practically the only female student, certainly the only female student over 25, and it was this lack of other women in the air that got me interested in the history of women in aviation. When I started digging, I soon discovered th

e fascinating stories of flight that I’ve used in my books.

My first flight at the controls of an aircraft took place at White Waltham airfield in southern England, which is where the Air Transport Auxiliary had their headquarters in World War II. Being surrounded by the history of the female aviators of World War II most definitely inspired me to write about them.

These three books work together beautifully as a trilogy but is there another Second World War Air Force that you would like to write about?

I’ve just recently discovered that there were women flying for the French Air Force before the German invasion of France, and that there were women flying for the Spanish Republican Air Force during the Spanish Civil War, so DEFINITELY YES!

Elizabeth, thank you for your time and fascinating answers!

Elizabeth Wein’s books are available through your local bookstore and online at bookshop.org. You can find out more about her and her books on her website.

Thank to Barrington Stoke for my review copies of The Last Hawk, Firebird and White Eagles.

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links to bookshop.org and will redirect you to their website. If you make a purchase I will make a very small commission at no extra cost to you and they also share their profits with independent bookshops around the UK.