The History Behind ‘Wolfwalkers’: an interview with award-winning film director Tomm Moore

Irish film studio Cartoon Saloon has already earned a reputation for creating beautiful and magical films that bring to life the folklore and landscape of Ireland. Founded in 1999 it is best known for its feature films The Secret of Kells and Song of the Sea. The studio also has received international acclaim for The Breadwinner and is now the creator of animated television series Puffin Rock and Dorg van Dang.

Their latest film, Wolfwalkers completes a trilogy directed by Cartoon Saloon co-founder Tomm Moore (The Secret of Kells was co-directed with Nora Twomey and Wolfwalkers was co-directed with Ross Stewart).

It is set around the Irish city of Kilkenny in Ireland during the mid-seventeenth century when Oliver Cromwell had begun his conquest of the country with his New Model Army. He ordered the deforestation of the woodland and hired professional wolf-hunters to eradicate Ireland’s large wolf population. The film tells the story of one such wolf-hunter, Bill, and his daughter Robyn who have arrived from England to make a home in Kilkenny. Determined to follow in her father’s footsteps, Robyn accidentally stumbles into the world of magical, shape-shifting Wolfwalker Mebh as she fights to preserve her way of life from the devastation caused by these new settlers. The character of Mebh was inspired by the long tradition of wolves in Irish folklore and many stories that tell of humans who could shapeshift into the form of a wolf.

Bill, Robyn and Mebh are all threatened by the puritanical authority of the English Lord Protector (a reference to the title held by Cromwell but the film never explicitly gives him a name) who is determined to conquer the people and countryside of Ireland by any means.

Wolfwalkers is the very first animated feature to have been made with the backing of Apple TV+ and, since its release in October 2020, has gone on to win, among others, five Annie Awards, a Dublin Film Critics’ Circle Award, a Hollywood Critics Association Award, a Los Angeles Film Critics Association Award, an American Film Institute Award, and a Satellite Award. It has also been nominated for countless other honours including seven Irish Animation Awards and the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature. The film is everything you could expect from Cartoon Saloon. It is visually stunning, beautifully written, moving, exciting and brings to life a historical story that is largely unknown.

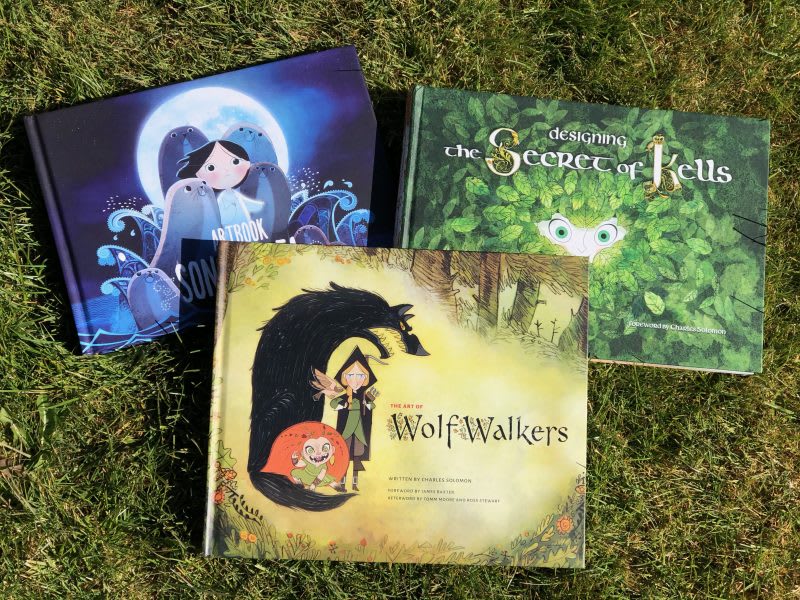

I’m a huge fan of the studio’s work and have been collecting art books and prints from them for years so I couldn’t have been more thrilled when Wolfwalker’s co-director Tomm Moore agreed to talk to me about the history behind the film. He not only shed light on the importance of folklore and history, but the important environmental ideas that inspired the original story.

Tomm, all three of the films you have directed are very anchored in Irish folklore and that folklore is such a part of the country’s history. I’d love to hear your thoughts on the original inspiration for Wolfwalkers and how it was shaped by historical events.

Ross and I came up with the idea about seven years ago when we were talking about what we might do as a third film. We thought three would be a nice number for these movies and, because The Secret of Kells had come out of Irish history and folklore, we thought we’d like to do something like that again. We also wanted to talk about speciesism and the whole concept that we see some animal species as ‘other’ and ‘bad’ or ‘barbaric’, so we put these human traits on them. Then it allows us to kill them and it’s a short step to doing that with humans. For example, you ascribe a certain aspect to say a snake, and then you call a person a snake. So we thought it spoke to a lot of polarisation that’s happening in the world now. I started my life in Newry in the North of Ireland, so I was conscious of that polarisation from a younger age maybe more than other people would have been. I moved to Kilkenny just before I started Primary school and Ross and I grew up together.

Kilkenny is very proud of being this medieval city and we were always told that it used to be the capital under the Catholic confederacy. It was centre of focus when Cromwell came and he tried to crush it just because of that. There was also a TV show, or a special or something called Wolfland, and it was about the fact that Ireland had been known as ‘Wolfland’. There was this notion [during the seventeenth century], again back to the speciesism, that if you killed all the wolves, you had tamed the country, there was an association between the wolves and the Irish people. We also thought about how in Song of The Sea, I was speaking to the fact that we were losing connection to the folklore [and] losing connection to our relationship with the environment. Fishermen were killing the seals just because they had suddenly changed their whole way of being in the world, from this older way that was about balance, to a way that was about maximising profits. It was interesting to think that at one point the wolves had been like the seals as well, so we wanted to speak to something else being lost beyond just the animal itself when the wolves and the forests were eradicated. So that’s a lot of the deeper themes [we wanted to include].

I’m from an Irish family so I’m aware of Cromwell’s reputation in the country and the dreadful damage he caused during the British Civil Wars but not many other people outside of Ireland know about it. On a wider scale this idea of a nation being invaded and conquered translates all over the world. Is that something that you took into account when you were initially creating the film, or were you very focused on an Irish story that just happened to to have a much wider relevance?

Yeah, there was a lot of discussion in the last seven years about colonialism, and where Ross and I started from a point of view of environmentalism, I do think there’s a discussion as well that we’re still living under this mindset that came about at that time period of domination and hierarchy between nations. Concepts of ‘Australian aborigines are savages’ and all that Rabbit Proof Fence stuff has been in the zeitgeist and people have been thinking about it and talking about. It became stronger as we worked on it.

But the starting point was more about our own experience and more about trying to speak about environmental issues rather than cultural, but I think the other themes crept in.

The story is set in Kilkenny at a very specific point in time. How much of building something historically accurate do you focus on when creating your fictional version of the past?

We immediately knew we wanted to use our artistic licence rather than make a documentary. We didn’t want to make an animated version of the Wolfland documentary; we wanted it to be a story. Maybe the biggest thing we shied away from was actually naming Cromwell because I think for a long time we were happy to call him Cromwell but I remember at a certain point Nora [Twomey, Tomm’s co-director on Cartoon Saloon’s first feature film The Secret of Kells] was saying you’re getting into dodgy territory. We knew that we simplified him as a character so much that he became more like this emblem of that kind of colonialism rather than actually Oliver Cromwell so we only refered to him as ‘Lord Protector’. And the same with the town. We have kind of landmarks of Kilkenny in there but we pushed the design to be much more fortress-like, almost like borrowing from images we saw of other towns of that time period and before in England and in France. [It was] kind of a shopping trip to use what was necessary for our story and we hope that people like yourself will be there for kids who are interested in the actual factual, definite history. It was something we were very wary of. We didn’t want to play so fast and loose that you end up with something like Pocahontas that seems to have done a disservice to the true story, but we didn’t want to be limited by it. We wanted it to be a fairytale. We set it in that time period but it’s an imagined, alternate version of that time.

You have signalled to more of the history though. The main antagonist is called ‘Lord Protector’, a reference to the title Cromwell held after the Civil War. At one point that character talks about ‘revolts in the south’ and that speaks to a much wider idea of Ireland being conquered, not just one specific narrative about Kilkenny. So you must have been conscious of telling a bigger story?

There was a bit of that as well in the discussions when we were writing it. Every locality has their ‘horrible Cromwell story’ and Will Collins [Wolfwalker’s screenwriter] is from Cork. He specifically named some town that Cromwell had done a job on and we simplified it down to ‘revolts in the south’ so that we only spoke to the broader conflict that was putting pressure on the Lord Protector and therefore pressure on Robyn and her dad.

In The Art of Wolfwalkers Will Collins explains how the historical settings made it easier to establish the limits of the universe in which the story was set. Did you find you were limited by the history or were you happy to trust Will to use it to create a story that could be adaptable to the themes you wanted to include?

Ah no, it was very collaborative even in the writing, so we went back and forwards. It didn’t feel limiting. It was always interesting. The more specificity you bring to something the more true it rings. I sometimes wonder if you went completely Game of Thrones and it was a totally imagined [story], not even anywhere in Ireland, it mightn’t have been as interesting. I think it’s more interesting that it was based on history. The writing process was a bit of a journey because we would go off on these little tributaries into the history stuff. So it was more a case of pulling it back to the central story rather than getting too lost in the history.

In all three of your movies we enter the magical worlds of characters whose existence is intertwined with their environments (Aisling in The Secret of Kells, Saoirse in Song of the Sea and Mebh in Wolfwalkers). But the main protagonists are the people who are learning about and seeing into their worlds (Brendan, Ben and Robyn respectively). Why did you choose to use an English girl as the main character in what is such an Irish story?

I think it was the heart of the original idea. You know, back to the speciesism. What would it take for a hunter to have empathy for what they’re hunting? How would Bill change? Early on Robyn was a little boy which we changed later, but when he was a boy we had him almost as ‘Robin’ to Bill’s ‘Batman’. They would hunt together and maybe Bill would end up shooting his own son and then Mebh would have to work her magic on him. But what kind of stuck was always that it needed to be that the person who had the biggest arc, the biggest change was always going to be Bill, but that Robyn would be the catalyst for that change, so I think making them English just made sense. And also there was a certain weariness of making yet another English bad, Irish good…have you got a friend?

[OK, so this was the point in the Zoom conversation when my four-year-old daughter decided to visit. I was surprised it took her this long but Tomm could not have been more lovely about the interruption. He had a great chat with her about her love of Cartoon Saloon’s Netflix series Puffin Rock and told her all about his three-year-old granddaughter, Mara. I did apologise but he responded that ‘It’s brilliant! I love this about the work from home! When Mara’s here I’m always so happy when she wanders in and sits on my knee.’]

So what I’d really like to know how you think these stories resonate with a contemporary audience?

I think for kids as well, and I think that was it…just on the English thing as well, we wanted it to not be too polarising in any way. We wanted to show that it was important that kids could see past differences. I remember when I was a kid in Northern Ireland, not knowing, not caring what anyone’s background was that I would play with. But sometimes there were older brothers and sisters who would ask me if I was Catholic or Protestant. And that was something we talked about a lot. Robyn and Mebh don’t care about the whole tribal thing behind them and I think that’s a big danger to the environment at the moment. Somehow people have aligned themselves on different political sides and somehow some of them have decided that it’s against their whole politics to care about the environment. We talked about Greta Thunberg and a young Jane Goodall [as inspiration] for Robyn because we want somebody like that young person who speaks across the divide and says it’s all our future that we’re endangering and it doesn’t matter what your politics are, we won’t have a planet to live on if we don’t take it seriously. So I think for a contemporary audience, that’s the most important thing. That we are able to look past the overall things that maybe make us seem different to each other and be able to get past that which is really challenging as an adult. [If] you go on twitter and everything and you just feel it’s hopeless. But you feel a little bit more hope with little ones, you know, they seem t

o care. And I’m sure your daughter and Mara would have much more in common than not in common. You don’t want to be preachy or anything but you kind of hope that there’s something positive in that.

And how do you see yourself in the overall role of continuing Irish history and folklore? Do you see yourself as a modern-day seanchaí with a responsibility for continuing these stories? [And yes, my hideous English butchery of the word ‘seanchaí’ did make Tomm smile.] Or would you prefer a more modern expression of what you do?

I suppose it was nice and I sort of feel a little bit free of that now. I don’t know what I’ll do next so I don’t feel like it’s my only thing I want to do as a storyteller. But I think it was nice to feel like, when my son was young was when I made the The Secret of Kells and Song of the Sea, I felt like I was somehow retelling the stories for his generation and then his generation would do something with virtual reality. But I don’t know, you’re just part of keeping the stories alive, keeping an interest in them, reimagining them. The only thing about the seanchaí was that they would tell the story to the audience they were speaking to and there was no written down gospel that this is it. So I would hope that we’d see more stories based on this sort of folklore from the next generation that don’t feel that these are the be all and and all, and that there’s another way to look at them. You just see yourself as the middle of a relay race, take it and then passing it on.

Tomm, thank you so much for your brilliant answers!

Wolfwalkers is available now exclusively on Apple TV+

Cartoon Saloon’s other feature films, The Secret of Kells, Song of the Sea and The Breadwinner are all available on online streaming services. You can also find them in Cartoon Saloon’s online store.

Puffin Rock is available exclusively to Netflix.

You can find out more about Cartoon Saloon’s work on their website here and buy merchandise from all of their films from their online store.